|

|

George H. Smith's

headstone at Old Gray Cemetery.

|

Born in London, England in 1828, his family came to the

United States and settled in New York while he was a young boy. He came of age

in the "Empire State," entered into the jewelry profession, and

married Annie M. Wintermute (see image 2—Annie

is buried next to the Smith family marblestone), who bore him a son. In 1859,

Smith uprooted his family and ventured south to the Queen City of the Mountains

as one of the last waves of northern and foreign-born migrants to arrive in

Knoxville before the Civil War.

|

|

Smith family plot at

Old Gray Cemetery, Knoxville. Smith's headstone is far right.

|

The 1850s marked an increase in Knoxville's ethnic

diversity revealed in the 1860 census as the foreign-born made up 22% of the

city's free adult male population. While many townspeople may have found this

trend disturbing as the majority of these newcomers were overwhelmingly poor

and unskilled, several of these immigrants, such as Smith, would come to

dominate Knoxville's postwar commercial and political affairs.

Smith prospered as Knoxville experienced a commercial

boom beginning in 1868 that lasted until a national recession—the Panic of 1873—slowed,

but did not halt, the city's remarkable economic growth. Smith acquired

considerable property throughout the city and built his home at the corner of

Walnut and Asylum (see pink arrow on 1871 map of Knoxville). A devout Christian

man, Smith and his family attended St. John's where he was an active member of

the Protestant Episcopal Church. He also was a member of the Masonic fraternity

holding the titles of "Worthy Master" and "Past High

Priest" of a local chapter (note the Masonic iconography on the Smith stone).

Annie died in 1871. Although grief stricken, Smith soon

found love with another woman, twenty-one years his junior, also named Annie.

Smith's marriage into the Ramage family was typical of many wealthy outsiders

before him, which solidified a union between Knoxville's native and non-native

elites. This bond among elites survived the Civil War, which divided many townspeople

lower on the socio-economic ladder, and was an instrumental factor in

Knoxville's rapid postwar economic growth as locals enthusiastically welcomed a

newer generation of Yankees from Ohio and New York especially, who brought with

them, like a generation before, much-needed energy, a vision of a New South,

and, most importantly, deep pockets as they arrived in the late 1860s. Smith's

second marriage produced a second son who was three years old on the morning of

December 20, 1876 when his father suddenly awoke to the terrifying sound of the

ringing of a fire bell.

Again, over time, accounts of Smith's

active involvement with the fire department as a concerned citizen who not only

advocated for the purchase of modern firefighting apparatus, but also answered

the alarm bell became blurred as the city gradually transitioned from a

voluntary fire department in the1870s and early 1880s into a professional paid

fire department in 1885. As such, many Knoxvillians in the late nineteenth and

early twentieth century simply referred to Smith, who died fighting a December

1876 blaze, as the city's first fallen firefighter. What soon became a

"fact" was subsequently published and republished in newspapers and

books. Hence, today you will find Smith's name on the Bell Buckle memorial to

the state's fallen firefighters as the first casualty among Tennessee's smoke

eaters.

What

happened 141 years ago today is a tragic story. Tragic for the death of a

prominent Knoxville merchant, husband, and father, but also an eye opening

warning that went largely unheeded by city fathers that they needed to bolster

their firefighting defenses in a rapidly expanding Gilded Age mountain city.

What follows is a portion of a first

draft that was written for chapter 2 of Knoxville's Million Dollar Fire, which

traces the evolution of Knoxville fire department:

A blast of cold

arctic air preceded the 1876 winter solstice by a day as the mercury fell below

twenty degrees in Knoxville. While most

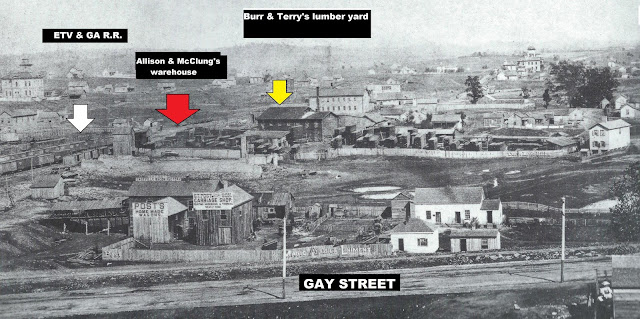

of the townspeople slept, the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad depot

was a busy hub of activity at half past two on the morning of December 20. The railroad’s passenger train number four

was departing as a small army of men loaded and unloaded a score of freight

cars that stood on the tracks underneath the elevated Gay Street bridge. Meanwhile, the watchman at Burr and Terry’s

lumber yard observed the bustling activity from his vantage point a block

directly east of the depot. Each

arriving and departing train represented the only break in his monotonous

routine of keeping a watchful eye on things around the yard. Suddenly he heard a loud cracking and

bursting noise from Allison and McClung’s warehouse which adjoined Burr and

Terry’s lumber yard alongside the tracks.

Upon closer examination, he found a bright flame that appeared to

emanate from the rear of the building.

Startled to see the advertised fireproof brick warehouse ablaze, the

watchman hastened to sound the alarm.

The fire gained significant ground before the alarm, relayed by word of

mouth, reached City Hall, the site of the fire alarm bell and the bulk of Knoxville's

firefighting apparatus. In short order,

the bell at City Hall announced the arrival of an industrializing city’s

greatest fear—the fire-fiend.

Suddenly the

terrific peals of the fire bell awoke the silence. Aroused from their slumbers, a number of

citizens raced from their homes to the scene of the fire. For a country deep in the throes of its

second industrial revolution, marked by an extraordinary series of

technological innovations, most municipal voluntary fire departments, which

were organized to safeguard their communities from devastation and economic

ruin, failed nationwide to keep pace with the rapid process of

urbanization. Thus lacking the means to

sufficiently combat fires that burned with regularity in densely built urban

areas and threatened both lives and property, the combustible Americans cities

of the nineteenth century required a massive response in firefighting

capacity. Fire was the responsibility of

citizens of all stripes. Thus merchant

princes and clerks, professional men and unskilled laborers alike, threw aside

whatever they were doing as soon as the fire bell tolled and raced to the scene

of the fire with their leather water buckets (municipal laws required every

property owner to keep two buckets filled with water at all times) or joined

teams to help pump the machines of the hand-drawn era of fire engines.

George H. Smith, prominent

businessman and property owner, did not hesitate for a moment to answer the

alarm as he leaped from his bed and hastily dressed himself. It was not at all uncommon to find Smith, an

active leader in the community, on the front lines fighting a fire. Firefighting not only demonstrated one’s

masculinity by testing their strength, courage, and speed, but also enabled

wealthy men to establish their civic virtue by exhibiting their leadership

capability. Smith was among the foremost

advocates of augmenting Knoxville’s firefighting efficiency. He frequently attended municipal meetings and

signed petitions to press city fathers to purchase the latest equipment and

repair any damaged apparatus. From time

to time, he even contributed out of pocket to help defray the costs for such

expenses and compensated voluntary firefighters for their bravery and

service. Smith grabbed his winter coat

and kissed his young bride goodbye as he stepped out on to his porch and

bundled against the biting cold.

Arriving at the

scene of the fire, Smith quickly surveyed the situation. Allison and McClung’s warehouse was

completely engulfed as flames flared and twisted angrily up into the night

sky. Various machinery, produce, and

other combustible materials stored inside the warehouse fueled the blaze. Across the open field that hosted itinerant

circuses and base ball matches, David Newman, the able engineer of the J.C.

Luttrell, stationed the city's lone steamer, a nearly ten year old Silsby fire

steam engine, along the bank of First Creek on Crozier Street so that he had an

available source of water to feed his engine.

But it would take time, as much as ten to fifteen minutes under the most

favorable conditions, before Newman could throw a solid stream of water at high

pressure on the fire. Moreover, the

department’s three hand engine companies struggled in the frigid conditions as

pipes froze solid thereby rendering the bulk of the city’s firefighting

apparatus impotent.

Col. Hugh Smith

then arrived on the scene and, as the owner of the largest quantity of goods

stored in the burning warehouse, assumed charge of directing efforts to salvage

any materials in and around the warehouse.

The conditions were much too dangerous to send anyone inside; therefore,

the Colonel dispatched small teams to clear a train of cars that stood on the

tracks in front of the warehouse. While

most of the cars were empty, burning embers landing near one coal filled car

threatened to ignite its combustible cargo.

George Smith and his team was tasked with rolling this car to a safe

distance down the track. As the men took

hold of the car, Smith stepped on the side of the track nearest the

warehouse. All of a sudden, a low and

distant rumble of thunder shook the ground.

A frightening cry sounded almost simultaneously. “The wall is falling!” The warning came too late for Smith. Trapped between the burning inferno and the

railroad car, he had nowhere to run once the brick wall, expanded by the fierce

heat, crackled and crumbled outward.

Hundreds of bricks rained down, burying Smith beneath a pile of crushing

debris. Dozens of hands immediately pitched

in to clear the mass of brick and mortar before them thus revealing Smith’s

lifeless body so covered in dust that he was not recognized until the jeweler’s

longtime friend Edward Jackson Sanford arrived on the scene and confirmed his

identify.

|

|

Present day site of the fire (to the

right of the tracks). Photograph taken on the Gay Street viaduct looking

northwest.

|

Before the smoldering ruins

of Allison and McClung’s warehouse had cooled, a cluster of influential

reform-minded citizens began to advocate for a commonsense approach to combat

fire and improve Knoxville’s fire protection.

A comprehensive report of the fire and an assessment of the voluntary fire

department revealed that it was woefully unprepared to protect Knoxville

against a massive conflagration. The key

findings of the report emphasized the department’s slow response time and outdated,

faulty equipment. Knoxville had failed

to modernize its fire defenses in light of an ever-changing and expanding urban

landscape.

The delay in the fire department’s

response exposed an inadequate system of alarm.

In an industrial age in which most urban fire departments had long

adopted fire alarm telegraph systems developed in the 1850s to more accurately

pinpoint the scene of a fire, Knoxville continued to rely on preindustrial

methods of alarm used since colonial times.

That most residents first learned of imminent danger from the tolling of

the city hall bell contributed to the slow response. Calls to repair the cracked bell that many

Knoxvillians on the outskirts of town claimed they could not hear had been

ignored for nearly five years. Despite recommendations

to purchase a modern telegraph alarm system, city leaders buried further

discussion in committee and justified their inaction in light of the lingering

regional and national recession. Another

twelve years passed before the city fathers approved the purchase of a modern

electric alarm system.

A second warning revealed by

the deadly fire concerned Knoxville’s antiquated fire apparatus. Although the fire department’s lone steamer

had performed admirably in arresting the flames in challenging conditions, the subfreezing

temperatures highlighted shortcomings of the voluntary fire department's hand-operated

fire engines. Whereas most cities made

the transition to steam prior to the Civil War and never looked back, Knoxville

city government had recently opted to purchase a third hand engine in favor of

another expensive and occasionally fickle steam fire engine. This bold decision, driven by fiscal probity,

ignored appeals from the fire chief, business leaders, and reformers for a

second steamer to help cover an expanding metropolis. The new fire apparatus that city fathers

christened the “Reliance” failed to live up to its name as it, and the other

two low pressure hand engines, proved counterproductive in inclement weather. Once more the city council balked and fell

back on habitual remedies. The city

fathers hedged their bets on a less costly solution to fire protection and

approved the purchase of four hundred feet of new hose. Moreover, they reorganized the department in

the hope that it would prove more efficient in answering future alarms.

The piecemeal response on the

part of Knoxville’s leaders revealed all the harbingers of trouble to come. All

too often, the clear warning signs of impending disaster were either dismissed

in the name of fiscal responsibility or ignored, swept under the rug of

borrowed time. Conservative boosters and

like-minded members of the press were notorious for constructing an alternate

script that glossed over the city’s outdated firefighting apparatus and the

destruction wrought by fire. Rather,

these stories emphasized individual acts of heroism and bravery—such as George Smith.

In the days that followed the

fatal fire of 1876, Knoxville’s city fathers, merchant princes, and the press

followed the same pattern of response to fire first exhibited by the town’s

pioneer settlers. This elite group

extolled the virtue and skill of its firefighters and their lone steamer, which

prevented the spread of fire and thus safeguarded lives and additional

properties. They focused their narrative

on a celebration of George Smith’s life, his civic virtue, and selfless

bravery. Smith’s heroism embodied the

classical republican notions of disinterested public service that nineteenth

century Americans had come to attribute to its political leaders as well as

voluntary and professional firemen. His

death, albeit tragic, represented a noble sacrifice to protect and secure the

lives and property of others. With each

new telling and retelling, Smith the jeweler filled with voluntaristic public

spirit who raced headfirst into danger without a moment’s doubt to assist the

fire department fight infernos blurred into Smith the fireman.

A close reading between the lines

of this narrative, however, revealed all the hazards to Knoxville connected

with fire. Be that as it may, the

warning signs eroded with the passage of time and a lack of devastating fires. A collective amnesia soon descended once

again over Knoxville, wiping out memories of the dangers posed by inadequate

fire protection as residents were lulled into a false sense of security. The fire-fiend was neither an infrequent

visitor nor did it discriminate between rich and poor as it consumed shanty

dwellings and two and three-story brick storehouses alike. But the fact that Knoxville remained

relatively small and spread out for much of its history minimized the potential

for catastrophic fires that consumed several blocks of residences and

businesses in many larger nineteenth century American industrialized

cities. The townspeople’s good fortune

bred complacency and a general lackadaisical attitude towards the enforcement

of fire codes.

A dangerous cocktail of

collective amnesia, complacency, and a general lackadaisical attitude towards

fire safety reform, while Knoxville's dense, urban landscape grew alarmingly, generated

the volatile environment that fueled Knoxville's Million Dollar Fire.

No comments:

Post a Comment