|

| David Newman, 1897 McClung Digital Collection |

Fighting fires and saving lives creates a close bond between firefighters. The fire department is itself a family. And often their own family members become firefighters. Most American fire departments include second, third, fourth, and so on generations of firefighters. That family tradition of firefighting is as alive today among Knoxville's smoke eaters as it was more than a century ago. A glance at the roster of its early twentieth century firefighters included in the diaries of Samuel Beckett Boyd II (Knoxville Fire Department Chief, 1900-1929), which are held in the Jack Lewis Collection at the McClung Historical Collection inside the East Tennessee History Center, reveals a department in which firefighting was already a family profession with father-son duos, brothers and cousins serving, and so on by the early 1900s.

The first family of Knoxville's professional firefighters begins with the Newmans. Born in Reidsville, North Carolina in 1833, David Newman, the family patriarch, came to Knoxville as a blacksmith and wagon maker. However, his young wife died in 1863, leaving him a widower with a young daughter (Mary). He quickly remarried that same year to a woman named Patience Eliza Martin. Together they had seven children--four daughters and three sons. Like most residents of Knoxville, Newman answered the fire alarm when the town's bell tolled. But he soon joined one of the antebellum town's volunteer fire companies in 1854. A half century later, his two youngest sons (Rufus Bearden & James Rodgers Newman) were veterans of the department and a grandson (Rufus B. Newman, Jr.) was beginning to take his first steps toward embarking on a career in the family business.

|

| David Newman's family listed in the 1880 Census, pg. 1 (Courtesy of Ancestry.com) Rufus B. Newman appears second from the bottom of the page. |

|

| David Newman's children listed in the 1880 Census, pg. 2 (Courtesy of Ancestry.com) James Rodgers Newman appears at the top of the page. |

As Knoxville entered the boom times of the 1880s and early 1890s, thanks in large part to a new influx of young, ambitious, visionary, and enterprising men seeking to harness the surrounding region's rail connections, labor pool, and abundant natural resources to carve out their respective fortunes, few of the city's residents looked back on its quaint, pre-modern frontier past (most of whom had no direct link to Knoxville's first families). But when the fire-fiend awoke from its slumber and blazed a path through the city, reporters sought out the grizzled, bearded veteran firefighter David Newman for perspective. They often asked Newman to recount the history of Knoxville's "fire laddies" and what it was like to fight fires before the Civil War, in an age when fire was fought by hand rather than steam.

|

| Fountain Fire Company No. 1, ca. 1860 (McClung Historical Digital Collection) |

In its antebellum days, Knoxville, like all cities, required all hands on deck to help snuff out a fire. Fire was the responsibility of citizens of all stripes. Thus merchant princes and clerks, professional men and unskilled laborers threw aside whatever they were doing as soon as the fire bell tolled, and rushed to the scene of the fire with two leather buckets. Armed with their buckets, some citizens did their civic duty by participating in the bucket brigade, men passing buckets filled with water to fill the hand fire engine's reservoir, while women passed the empty buckets back to the source of the water. Other men joined teams to pump the hand machines. Newman was often found in the center of the action, vigorously pumping the engine to put out the fire. When the city fathers purchased two new hand fire engines and formally organized new volunteer companies in the 1850s, Newman joined the Fountain Fire Company, No. 1.

A rash of fires that erupted in various parts of town in the mid to late 1850s, suspected to be the work of an unknown arsonist, pushed city fathers to begin purchasing modern fire fighting apparatus. By all measures, with these new, much-needed acquisitions, Knoxville's fire fighting capacity was sufficient to protect the burgeoning antebellum town on the eve of the United States Civil War. However, the war derailed the progressive action taken by Knoxville leaders to bolster its fire defenses. Knoxville's phenomenal postwar growth, spurred by an influx of freed blacks and whites from the surrounding valleys and mountains, required more and more city services. An antebellum town in 1860, which had more than doubled to 5,300 in a span of ten years, quickly matured into a city that boasted 8,682 residents in 1870. Between 1870 and 1900, the city nearly quadrupled to 32,673. The financial well-being of Knoxville constituted the most pressing issue facing its leaders as they struggled to balance the books while attempting to improve streets and provide better street lighting, water, and police and fire protection. The fire department seemed to get shortchanged as immediate postwar monies were allocated in favor of a new city hall and additional policeman to remedy an epidemic of thefts, burglaries, robberies, and murders. This massive ballooning of government spending further increased Knoxville's debt. Consequently, in order to purchase much-needed fire apparatus, city fathers would need to solicit funds from community leaders, just as their antebellum ancestors had done so to better protect the city from the fire-fiend.

Knoxville belatedly entered the horse-drawn era of firefighting with the acquisition of its first steam engine in 1867. The debt-ridden city government was forced to spend money to deal with the threat of fire as their city grew at an alarming rate. Thus city leaders agreed to pay half of the cost of a new steam fire engine if the community could manage to raise the other half. The engine itself, a Silsby rotary steam fire engine built in Seneca Falls, New York, was capable of discharging five hundred pounds of water per minute, cost $5,500. However, the purchase of additional firefighting apparatus and two mules to pull the four thousand pound steamer brought the total cost to $8,750. The new engine was christened the "J.C. Luttrell" after Knoxville's popular mayor, who not only had held the post since 1859, but also proved to be a staunch advocate of improved fire protection. David Newman, designated as a stoker, was tasked with feeding fuel (coal) to the firebox to get the steam up before water could be played on a fire. Among some of the new purchases included in the total cost were new uniforms consisting of red flannel jackets double breasted with black velvet cuffs and collars for the regular firemen. Officers were designated by marks on their left arm. Engineers, the ones with the specialized knowledge trusted to run and manage the expensive steam engines, had a uniform consisting of dark flannel jackets trimmed and made the same as the others. Newman, still a member of the postwar voluntary fire department would soon receive one of these latter uniforms.

Following a devastating conflagration in March 1869, the worst fire in the city's history to date, causing more than sixty thousand dollars in damages, Knoxville's leaders made several adjustments to the city's fire department. The various companies were reorganized in 1870, at which point the election of the fire department's officers were to be held on a regular basis (initially every six months), and David Newman was elected first engineer. Newman, a favorite among the firemen and known by city leaders to be a competent and trustworthy engineer to run and manage the city's expensive engine, was regularly reelected without any opposition.

In 1878, according to the records of the Knoxville City Council minute books, Newman requested city leaders to furnish him with $15 so that he could install either a telegraph or telephone line from City Hall to his home to arouse him in case of a fire as he could no longer clearly hear the cracked City Hall bell from his home. When Knoxville purchased a new Silsby steam fire engine (the "Alex Allison," named after a popular progressive Democratic city alderman, who, as chairman of the police and fire committee had negotiated the contract) at the bargain price of $3200 and it arrived in December 1878, Newman was quickly reassigned from the "J.C. Luttrell" to take possession of the city's newest engine. In early 1880, considering the knowledge of steam engines and hydraulics required to be an engineer, city leaders agreed to pay an annual salary to only the fire department's engineers. The engineer of the "J.C. Luttrell" was paid $110 a year whereas the veteran Newman was paid $150. When city leaders reorganized the fire department again in March 1883 and agreed to pay its volunteer firemen an annual salary, Newman continued to receive $150, a rate which made him the highest paid fireman (the chief only earned $100 a year).

In early 1885, city leaders reorganized the fire department again, this time abandoning the voluntary fire department model in favor of a professional, paid fire department. Even then, Newman remained the highest paid fireman on staff at $75 a month. Herman Schenck, a painter by trade and a regular member of the voluntary fire department was elected to become the first paid chief at $50 per month. In 1889, however, the annual salaries of the fire department personnel was readjusted at which point the chief's salary was raised to $83.33 per month while the engineer's salary remained fixed at $75. Still, the engineer, the man responsible for running and managing the steam engine, captured the public's attention and the easily recognizable David Newman, with his long Rip Van Winkle-like white beard, was a local hero.

As Knoxville entered the 1890s, the boom times slowed as another economic depression, the Panic of 1893, swept over the nation, engulfing the Mountain City. Businesses came to a screeching halt and the city fathers tightened their belts. In such times, city leaders adopted fiscal probity and thus no new expenses were allocated for the fire department. Many Knoxvillians felt confident that their modern firefighting force, which consisted of three steam fire engines (a brand new engine, the "M.E. Thompson" purchased in 1892, the "Alex Allison" with 15 years of service, and the "J.C. Luttrell" in semi-retirement with 26 years of service), a hook and ladder truck, two hose reels, a state of the art Gaynor Electric Fire Alarm, eleven horses, and twenty-four firemen, could sufficiently protect the city's residents and property. Yet Newman often warned that the city had been spared the great conflagrations that regularly destroyed large portions of other Gilded Age American cities such as Chicago and Boston. In the 1890s, the Knoxville Tribune became the voice of progressive Democratic reformers and quoted Newman to warn Knoxvillians that time was not on their side when it came to further bolstering their fire defenses and shoring up glaring gaps in the city's fire codes.

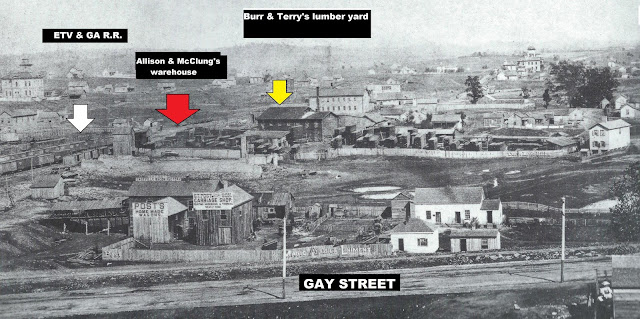

To be sure, Knoxville did not totally escape the fire-fiend untouched. There were approximately 60-80 fires a year throughout the early to mid-1890s, but few involved multiple structures. Annual losses due to fires jumped significantly throughout the 1890s, doubling to about $85,000 a year. There were near misses, in the case of a fire that broke out along Gay Street in the central business district in 1895; however, none of these fires met the definition of a cataclysmic conflagration until the Million Dollar Fire of 1897. By that time, Newman's youngest son, James Rodgers Newman, had been elected to join the force. James, like his father, was mechanically inclined and thus he served as an assistant engineer on the "M.E. Thompson." A life long bachelor, he devoted his life to both of his families--splitting time living at home and the various fire stations in which he was based.

On the morning of the Million Dollar Fire, the Newmans were tasked with making sure the "M.E. Thompson" and the "Alex Allison" kept running efficiently, putting a steady stream of water on the fire as it swept in both a northerly and southerly direction, devouring most of the 300 and 400 blocks on the east side of Gay Street. All engines were needed (the city also called on Chattanooga for help--they sent a steam engine and a crew to help assist the fire--more on that incredible story in the book!). The "J.C. Luttrell," affectionately named "Old Brassy" by the firefighters, was peacefully slumbering in the city stables along State Street when the fire broke out. Chief James McIntosh ordered a number of firemen to make a dash toward the State Street Stables to fetch "Old Brassy," which had rarely been used after the purchase of the "M.E. Thompson." Few thought that the old workhorse would fire up; however, it did. "Old Brassy" was only able to withstand ninety-five pounds of steam, but every little bit was critical as it appeared the whole east side of Gay Street and surrounding structures may go up in a cloud of smoke. Throughout the fire, both Newmans regularly checked on "Old Brassy," which kept plugging away at the northern end of the fire. As David and James oversaw the department's steam engines, Rufus Bearden Newman, David's second youngest son and a lineman with the East Tennessee Telephone Company, risked his life on numerous occasions as he raced into all but four of the burning buildings to save the company's telephones.

By noon the fire was all but contained. Some eighteen structures were in ruins or damaged with the total of losses estimated at $1.25 million dollars. After nearly twelve hours of fighting the fire, the "M.E. Thompson" and its crew (including both Newmans), returned to its headquarters at City Hall for a much-needed rest while the "Alex Allison" and "Old Brassy" kept a steady stream of water on the smoldering ruins which burned for nearly a week. A reporter with the Knoxville Tribune stationed at City Hall asked David Newman to put the fire into perspective. The tired eyes of the 43-year veteran firefighter gazed out toward Wall Street for a few seconds before he turned toward the reporter and said, "This is the biggest disaster I ever saw or ever expect to see in this world."

In the aftermath of the fire, the Newmans came up with creative solutions to resolve some of the city's fire safety issues. Progressive reformers bemoaned a negligent culture of enforcement of the city's fire codes. A lack of fire escapes was blamed for the deaths of three lodgers in the Hotel Knox and the numerous injuries incurred by those forced to jump from the third story windows of the hotel for safety on the rooftop of the one and half story E.P. King building below. Three weeks after the fire, pedestrians passing by City Hall were shocked to see a man jump from one of its third story windows with a rope fastened around his waist. When the rope caught, he then descended slowly down to safety on the street below thanks to a pulley system. The man with the rope around his waist was James Rodgers Newman. He fielded questions from the hundreds of onlookers who had descended on Market Square eager to learn of his new invention.

As the weeks turned into months following the fire, city leaders and progressive reformers debated as to the best course of action to improve the city's fire defenses while also being fiscally responsible. The city had recently spent $27,000 to build a new Market House and the city coffers were running low of funds. J. R. Newman once again applied his mechanical skills to build the department its first chemical engine. The chemical engine, built to be light weight and pulled by one horse, was a revolution in firefighting, meant to save property, reducing the damages incurred by water used to douse flames. Newman tested the engine twice on November 22, 1897 to huge crowds that turned out to witness the new machine. In its first test, Newman's chemical engine tamed the flames within two minutes and had extinguished them completely in three minutes. The flames were allowed to burn longer during the second test, which was then put out within one minute. Newman then continued to spray the ruins, fully discharging the 32 gallon tank of its chemical mixture in six minutes. The city fathers on hand were satisfied by Newman's test and soon appropriated money for the purchase of a larger chemical engine with two 50 gallon tanks. After the successful tests, Newman christened his chemical engine the "David Newman No. 1" in honor of his father. From time to time reports of the "David Newman" in action appeared in the papers. The "Newman" was credited by saving a house that erupted on fire in April 1898.

By that time, neither David nor James Rodgers Newman were listed on the fire department's rosters. Politics had dealt the Newmans a bad hand. In January 1898, the Republicans swept into power, claiming the city government. Consequently, their victories led to the removal of Democratic firemen in favor of Republicans. Despite the cries of progressive reformers that sought to keep its capable, veteran firemen, the Newmans were both turned out of the department by the political guillotine. Without work, David and James R. joined John William Newman, the eldest son, in the laundry business. Together, David and Sons managed the Palace Steam Laundry located on 110 Mabry (later 110 E. Vine Ave.). David Newman remained in the laundry business until he died of bronchitis in 1912. However, J. R. Newman would return to the fire department as a stoker and later mechanical engineer under a more favorable political climate in 1905. Newman remained in the service until pulmonary tuberculosis resulted in his death at the age of 51 in 1924. Newman was interred near his father in the family plot at Old Gray Cemetery.

Shortly before David Newman passed, he helped organize the Park City Fire Department. Its first chief was his son, Rufus Bearden Newman, Sr., who he also trained to be a fireman. Rufus, already in his early 40s, served as chief until 1917, when he became captain, a post he held until he retired in his early 70s. He died on November 3, 1955 and is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery (his grave marker lists him as Rufe rather than Rufus). David Newman's grandson, Rufus B. Newman, Jr., joined the Park City Fire Department in 1911 as a pipeman and went on to serve a long career in the family business.

As Knoxville entered the 1890s, the boom times slowed as another economic depression, the Panic of 1893, swept over the nation, engulfing the Mountain City. Businesses came to a screeching halt and the city fathers tightened their belts. In such times, city leaders adopted fiscal probity and thus no new expenses were allocated for the fire department. Many Knoxvillians felt confident that their modern firefighting force, which consisted of three steam fire engines (a brand new engine, the "M.E. Thompson" purchased in 1892, the "Alex Allison" with 15 years of service, and the "J.C. Luttrell" in semi-retirement with 26 years of service), a hook and ladder truck, two hose reels, a state of the art Gaynor Electric Fire Alarm, eleven horses, and twenty-four firemen, could sufficiently protect the city's residents and property. Yet Newman often warned that the city had been spared the great conflagrations that regularly destroyed large portions of other Gilded Age American cities such as Chicago and Boston. In the 1890s, the Knoxville Tribune became the voice of progressive Democratic reformers and quoted Newman to warn Knoxvillians that time was not on their side when it came to further bolstering their fire defenses and shoring up glaring gaps in the city's fire codes.

|

| James Rodgers Newman, 1897 McClung Digital Collection |

On the morning of the Million Dollar Fire, the Newmans were tasked with making sure the "M.E. Thompson" and the "Alex Allison" kept running efficiently, putting a steady stream of water on the fire as it swept in both a northerly and southerly direction, devouring most of the 300 and 400 blocks on the east side of Gay Street. All engines were needed (the city also called on Chattanooga for help--they sent a steam engine and a crew to help assist the fire--more on that incredible story in the book!). The "J.C. Luttrell," affectionately named "Old Brassy" by the firefighters, was peacefully slumbering in the city stables along State Street when the fire broke out. Chief James McIntosh ordered a number of firemen to make a dash toward the State Street Stables to fetch "Old Brassy," which had rarely been used after the purchase of the "M.E. Thompson." Few thought that the old workhorse would fire up; however, it did. "Old Brassy" was only able to withstand ninety-five pounds of steam, but every little bit was critical as it appeared the whole east side of Gay Street and surrounding structures may go up in a cloud of smoke. Throughout the fire, both Newmans regularly checked on "Old Brassy," which kept plugging away at the northern end of the fire. As David and James oversaw the department's steam engines, Rufus Bearden Newman, David's second youngest son and a lineman with the East Tennessee Telephone Company, risked his life on numerous occasions as he raced into all but four of the burning buildings to save the company's telephones.

By noon the fire was all but contained. Some eighteen structures were in ruins or damaged with the total of losses estimated at $1.25 million dollars. After nearly twelve hours of fighting the fire, the "M.E. Thompson" and its crew (including both Newmans), returned to its headquarters at City Hall for a much-needed rest while the "Alex Allison" and "Old Brassy" kept a steady stream of water on the smoldering ruins which burned for nearly a week. A reporter with the Knoxville Tribune stationed at City Hall asked David Newman to put the fire into perspective. The tired eyes of the 43-year veteran firefighter gazed out toward Wall Street for a few seconds before he turned toward the reporter and said, "This is the biggest disaster I ever saw or ever expect to see in this world."

|

| David Newman, Knoxville Journal (April 10, 1897) |

In the aftermath of the fire, the Newmans came up with creative solutions to resolve some of the city's fire safety issues. Progressive reformers bemoaned a negligent culture of enforcement of the city's fire codes. A lack of fire escapes was blamed for the deaths of three lodgers in the Hotel Knox and the numerous injuries incurred by those forced to jump from the third story windows of the hotel for safety on the rooftop of the one and half story E.P. King building below. Three weeks after the fire, pedestrians passing by City Hall were shocked to see a man jump from one of its third story windows with a rope fastened around his waist. When the rope caught, he then descended slowly down to safety on the street below thanks to a pulley system. The man with the rope around his waist was James Rodgers Newman. He fielded questions from the hundreds of onlookers who had descended on Market Square eager to learn of his new invention.

|

| This chemical engine is similar to the "David Newman No. 1" built by J.R. Newman (Vintage Fire Museum, Jeffersonville, IN) |

|

| David Newman interred at Old Gray Cemetery |

|

| J.R. Newman interred at Old Gray Cemetery |

|

| David Newman's two wives are buried next to him in the family plot at Old Gray Cemetery. |